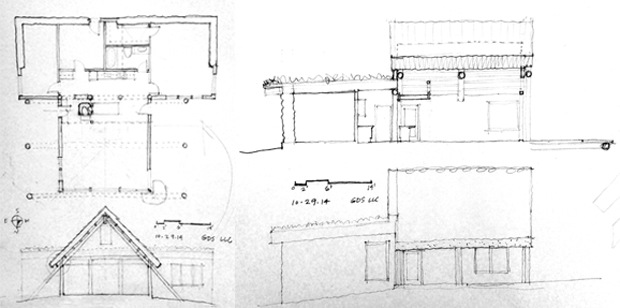

I made these sketches for my longtime collaborator and friend, Polly Bart. After a couple of decades as a green builder, she is building a house for herself using all natural and salvaged materials, including trees harvested from her land, strawbale walls, a green roof, and—possibly best of all—a thatched roof over the main living room’s steeply pitched log structure. Last month, the master thatcher came from Ireland to put up the roof. The photos of it are stunning. (Scroll down this post for a slideshow of six images, or follow this link for more.)

I made these sketches for my longtime collaborator and friend, Polly Bart. After a couple of decades as a green builder, she is building a house for herself using all natural and salvaged materials, including trees harvested from her land, strawbale walls, a green roof, and—possibly best of all—a thatched roof over the main living room’s steeply pitched log structure. Last month, the master thatcher came from Ireland to put up the roof. The photos of it are stunning. (Scroll down this post for a slideshow of six images, or follow this link for more.)

This morning, I awoke from a dream of her roof, thinking about the differences between a roof like this and conventional construction. Modern construction technology favors industrial materials put up in layers, each with its specialized purpose: structure, enclosure, water shedding, waterproofing, insulation, and to bridge and/or seal thermal movement of the different materials. Thatch, by itself, takes care of all of those purposes save the structure. Great skill and long training are required to do it correctly.

In modern buildings, cost is broken into two parts: materials and labor. Labor is usually the greater cost, so materials are chosen to reduce and minimize it. To keep the overall cost as low as possible, it’s especially important to minimize the amount of skilled labor. This equation comes from an industrial assembly-line model, where it’s preferable from a cost and a time standpoint to have more unskilled laborers doing small, repetitive actions, than to have skilled craftsmen doing painstaking, specialized work.

The result is an unfortunate characteristic of most modern construction: assemblies of industrial components, rather than the human imprint of craft. This is what William Morris and his ilk worried and warned about back in the 19th century.

Thatching is a wonderfully subversive craft, in that it turns the modern equation on its head. Thatching is all labor. The material, an invasive weed in aquatic landscapes (water reed, Phragmites australis), is free for the taking. And thatch does everything: insulates and sheds water and bridges thermal movement. Best of all, it’s a gorgeous, long-lasting roof. (There’s an interesting article about the history and conservation of this craft here. And on Wikipedia.)

As an architect, my clients—from homeowners to church building committees to college financial V.P.s—all stress the need for low- or no-maintenance construction. As though building something new was trouble enough; they shouldn’t have to take care of it, too. The expectation is that modern materials and construction techniques have somehow conquered physics and time, making wear and tear a thing of the past. The need to maintain a building is somehow seen as a failure in the face of modern advancements, a passé anomaly of a by-gone age.

In this era of 3-D printing, such whiz-bang technology keeps us more and more isolated from the truth, the material reality of life on this physical planet, with its laws of thermodynamics and gravity. The need for maintenance stems from the very real interaction of a building with the earthly conditions of sun, wind, rain, snow, heat and cold.

The sad fact is that many modern materials are less sturdy and long-lasting than their organic predecessors. Plastic is notoriously fragile in the glare of the sun’s powerful UV rays, unless chemical stabilizers are added. The mantra, Better living through chemistry, drives scientists to find admixtures that increase longevity, retard the spread of flames, increase plasticity, lessen brittleness, prevent outgassing, or otherwise improve inherently unstable materials. Brick, on the other hand, is essentially baked clay and can stand for hundreds of years. It’s also fireproof and water resistant.

Likewise, thatched roofs have been in service around the world for many hundreds of years, with regular, though minimal, upkeep. Asphalt shingles, the typical roof on a suburban American house, last at best 35 to 50 years, if the warranty is to be believed. Typically, south-facing shingle roofs wear out sooner, again because the sun is murder on most building materials. There’s a case to be made, I suppose, that after one or two roof replacements, the rest of the house is likely ready to be torn down anyway. Another sign of the temporary, throwaway world we have been building for the last sixty years.

In my very first course in Architecture school, our professor asked this question: “What does it mean to make a mark upon the land?” Our role as creators and then caretakers of our buildings used to be seen as an extension of our relationship with the natural world. I take it as a hopeful sign that more people seem to be interested in learning these old crafts. Building is not merely a means to an end. It is a path to deeper relationship with a place, and with the history and traditions of the materials and building crafts native to that place. It is my belief—and hope—that repairing our relationship with the craft of building will help us to revise our stories away from separate superiority to nature, and towards belonging and co-creation with the whole animate world around us.

Pingback: Thatching Our Way to a New Story of Relationship - Greenbuilders.com

Thank you for your refreshing post. I am reminded of my search for a house years ago in a new community in the NE USA. There were NO brick houses! The realtor hired by the University recruiting us couldn’t understand why the lack of brick over new plastic siding was an issue. We choose a more permanent community to settle and declined the job offered.

Hi Julie,

Thanks for an interesting and informative post. My girlfriend and I are hoping to build our own place from cob–or perhaps some kind of Oehler structure or strawbale house–some time down the road, on our property here in the mountains of North Carolina.

I’m enjoying your blog a lot, and I also really enjoyed your piece in Dark Mountain. Keep up the good work and best of luck to you in 2016!

Your fellow Dark Mountain contributor (and ex-Baltimorean)

Matt Miles

Hi, Matt,

Great to hear from you and thanks for reading. I love these new connections via Dark Mountain – my tribe! Will definitely check out your piece. Stay in touch.

Cheers!